A permissive software license, sometimes also called BSD-like or BSD-style license,[1] is a free-software license with only minimal restrictions on how the software can be used, modified, and redistributed, usually including a warranty disclaimer. Examples include the GNU All-permissive License, MIT License, BSD licenses, Apple Public Source License and Apache license. As of 2016,[update] the most popular free-software license is the permissive MIT license.[2][3]

The following is the full text of the simple GNU All-permissive License:

Copyright <YEAR>, <AUTHORS>

Copying and distribution of this file, with or without modification, are permitted in any medium without royalty, provided the copyright notice and this notice are preserved. This file is offered as-is, without any warranty.

The Open Source Initiative defines a permissive software license as a "non-copyleft license that guarantees the freedoms to use, modify and redistribute".[6]GitHub's choosealicense website describes the permissive MIT license as "[letting] people do anything they want with your code as long as they provide attribution back to you and don’t hold you liable."[7]California Western School of Law's newmediarights.com defined them as follows: "The ‘BSD-like’ licenses such as the BSD, MIT and Apache licenses are extremely permissive, requiring little more than attributing the original portions of the licensed code to the original developers in your own code and/or documentation."[1]

| Public domain & equivalents | Permissive license | Copyleft (protective license) | Noncommercial license | Proprietary license | Trade secret | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Grants all rights | Grants use rights, including right to relicense (allows proprietization, license compatibility) | Grants use rights, forbids proprietization | Grants rights for noncommercial use only. May be combined with copyleft. | Traditional use of copyright; no rights need be granted | No information made public |

| Software | PD, CC0 | BSD, MIT, Apache | GPL, AGPL | JRL, AFPL | proprietary software, no public license | private, internal software |

| Other creative works | PD, CC0 | CC-BY | CC-BY-SA | CC-BY-NC | Copyright, no public license | unpublished |

Copyleft licenses generally require the reciprocal publication of the source code of any modified versions under the original work's copyleft license.[8][9] Permissive licenses, in contrast, do not try to guarantee that modified versions of the software will remain free and publicly available, generally requiring only that the original copyright notice be retained.[1] As a result, derivative works, or future versions, of permissively-licensed software can be released as proprietary software.[10]

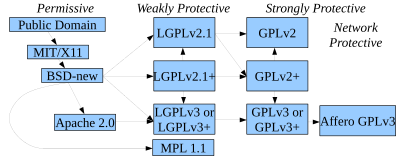

Permissive licenses offer more extensive license compatibility than copyleft licenses, which cannot generally be freely combined and mixed, because their reciprocity requirements conflict with each other.[11][12][13][14][15]

Computer Associates Int'l v. Altai used the term "public domain" to refer to works that have become widely shared and distributed under permission, rather than work that was deliberately put into the public domain. However, permissive licenses are not actually equivalent to releasing a work into the public domain.

Permissive licenses often do stipulate some limited requirements, such as that the original authors must be credited (attribution). If a work is truly in the public domain, this is usually not legally required, but a United States copyright registration requires disclosing material that has been previously published,[16] and attribution may still be considered an ethical requirement in academia.

Advocates of permissive licenses often recommend against attempting to release software to the public domain, on the grounds that this can be legally problematic in some jurisdictions.[17][18]Public-domain-equivalent licenses are an attempt to solve this problem, providing a fallback permissive license for cases where renunciation of copyright is not legally possible, and sometimes also including a disclaimer of warranties similar to most permissive licenses.

In general permissive licenses have good license compatibility with most other software licenses in most situations.[11][12]

Due to their non-restrictiveness, most permissive software licenses are even compatible with copyleft licenses, which are incompatible with most other licenses. Some older permissive licenses, such as the 4-clause BSD license, the PHP License, and the OpenSSL License, have clauses requiring advertising materials to credit the copyright holder, which made them incompatible with copyleft licenses. Popular modern permissive licenses, however, such as the MIT License, the 3-clause BSD license and the zlib license, don't include advertising clauses and are generally compatible with copyleft licenses.

Some licenses do not allow derived works to add a restriction that says a redistributor cannot add more restrictions. Examples include the CDDL and MsPL. However such restrictions also make the license incompatible with permissive free-software licenses.[citation needed]

While they have been in use since the mid-1980s,[20] several authors noted an increase in the popularity of permissive licenses during the 2010s.[21][22][23][24]

As of 2015,[update] the MIT License, a permissive license, is the most popular free software license, followed by GPLv2.[2][3]

Berkeley had what we called "copycenter," which is "take it down to the copy center and make as many copies as you want."

— Marshall Kirk McKusick, [25]

Copycenter is a term originally used to explain the modified BSD license, a permissive free-software license. The term was presented by computer scientist and Berkeley Software Distribution (BSD) contributor Marshall Kirk McKusick at a BSD conference in 1999. It is a word play on copyright, copyleft and copy center.[25][26]

In the Free Software Foundation's guide to license compatibility and relicensing, Richard Stallman defines permissive licenses as "pushover licenses", comparing them to those people who "can't say no", because they are seen as granting a right to "deny freedom to others."[27] The Foundation recommends pushover licenses only for small programs, below 300 lines of code, where "the benefits provided by copyleft are usually too small to justify the inconvenience of making sure a copy of the license always accompanies the software".[28]

1. MIT license 24%, 2. GNU General Public License (GPL) 2.0 23%, 3. Apache License 16%, 4. GNU General Public License (GPL) 3.0 9%, 5. BSD License 2.0 (3-clause, New or Revised) License 6%, 6. GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) 2.1 5%, 7. Artistic License (Perl) 4%, 8. GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) 3.0 2%, 9. Microsoft Public License 2%, 10. Eclipse Public License (EPL) 2%

"1 MIT 44.69%, 2 Other 15.68%, 3 GPLv2 12.96%, 4 Apache 11.19%, 5 GPLv3 8.88%, 6 BSD 3-clause 4.53%, 7 Unlicense 1.87%, 8 BSD 2-clause 1.70%, 9 LGPLv3 1.30%, 10 AGPLv3 1.05%

The licenses for distributing free or open source software (FOSS) are divided in two families: permissive and copyleft. Permissive licenses (BSD, MIT, X11, Apache, Zope) are generally compatible and interoperable with most other licenses, tolerating to merge, combine or improve the covered code and to re-distribute it under many licenses (including non-free or “proprietary”).

Permissive licensing simplifies things One reason the business world, and more and more developers [...], favor permissive licenses is in the simplicity of reuse. The license usually only pertains to the source code that is licensed and makes no attempt to infer any conditions upon any other component, and because of this there is no need to define what constitutes a derived work. I have also never seen a license compatibility chart for permissive licenses; it seems that they are all compatible.

No. Some of the requirements in GPLv3, such as the requirement to provide Installation Information, do not exist in GPLv2. As a result, the licenses are not compatible: if you tried to combine code released under both these licenses, you would violate section 6 of GPLv2. However, if code is released under GPL "version 2 or later," that is compatible with GPLv3 because GPLv3 is one of the options it permits.

GPLv3 broke "the" GPL into incompatible forks that can't share code.

In some jurisdictions, it is doubtful whether voluntarily placing one's own work into the public domain is legally possible. For that reason, to make any substantial body of code free, it is preferable to state the copyright and put it under an ISC or BSD license instead of attempting to release it into the public domain.

Also at the time I did not realize, having lived my whole life in the United States, which is, you know, under British common law, where the public domain is something that’s recognized. I did not realize that there were a lot of jurisdictions in the world where it’s difficult or impossible for someone to place their works in the public domain. I didn’t know. So that’s a complication.

[There's] a good argument to be made that the MIT License, also called the X Consortium or X11 License at the time, crystallized with X11 in 1987, and that's the best date to use. You could argue it was created in 1985 with possible adjustments over the next couple of years.

The GPL is still the world's most popular open-source license but it's declining in use, while permissive licenses are gaining more fans, and some developers are choosing to release code without any license at all.

In general, lax permissive licenses (modified BSD, X11, Expat, Apache, Python, etc.) are compatible with each other. That's because they have no requirements about other code that is added to the program. They even permit putting the entire program (perhaps with changes) into a proprietary software product; thus, we call them "pushover licenses" because they can't say "no" when one user tries to deny freedom to others.

By: Wikipedia.org

Edited: 2021-06-18 15:09:51

Source: Wikipedia.org