| |

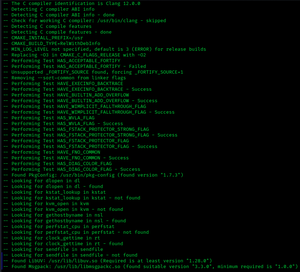

Clang being used to compile Neovim | |

| Original author(s) | Chris Lattner |

|---|---|

| Developer(s) | LLVM Developer Group |

| Initial release | September 26, 2007[1] |

| Stable release | 12.0.0[2]

/ April 14, 2021 |

| Repository | |

| Written in | C++ |

| Operating system | Unix-like |

| Platform | LLVM (ARMv7, AArch64, IA-32, x64, ppc64le)[3] |

| Type | Compiler |

| License | |

| Website | clang |

Clang /ˈklæŋ/[5] is a compiler front end for the C, C++, Objective-C and Objective-C++ programming languages, as well as the OpenMP,[6]OpenCL, RenderScript, CUDA and HIP[7] frameworks. It uses the LLVM compiler infrastructure as its back end and has been part of the LLVM release cycle since LLVM 2.6.

It is designed to act as a drop-in replacement for the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), supporting most of its compilation flags and unofficial language extensions.[8][9] Its contributors include Apple, Microsoft, Google, ARM, Sony, Intel and Advanced Micro Devices (AMD). It is open-source software,[10] with source code released under the University of Illinois/NCSA License, a permissive free software licence. Since v9.0.0, it was relicensed to the Apache License 2.0 with LLVM Exceptions.[4]

Clang 12, the latest major version of Clang as of April 2021, has full support for all published C++ standards up to C++17, implements most features of C++20, and adds initial support for the upcoming C++23 standard.[11] Since v6.0.0, Clang compiles C++ using the GNU++14 dialect by default, which includes features from the C++14 standard and conforming GNU extensions.[12]

The Clang project includes the Clang front end, a static analyzer, and several code analysis tools.[13]

Starting in 2005, Apple Inc. made extensive use of LLVM in a number of commercial products,[14] including the iOS SDK and Xcode 3.1.

One of the first uses of LLVM was an OpenGL code compiler for OS X that converts OpenGL calls into more fundamental calls for graphics processing units (GPU) that do not support certain features. This allowed Apple to support OpenGL on computers using Intel Graphics Media Accelerator (GMA) chipsets, increasing performance on those machines.[15] For GPUs that support it, the code is compiled to fully exploit the underlying hardware, but on GMA machines, LLVM compiles the same OpenGL code into subroutines to ensure continued proper function.

LLVM was intended originally to use GCC's front end, but GCC turned out to cause some problems for developers of LLVM and at Apple. The GCC source code is a large and somewhat cumbersome system for developers to work with; as one long-time GCC developer put it referring to LLVM, "Trying to make the hippo dance is not really a lot of fun".[16]

Apple software makes heavy use of Objective-C, but the Objective-C front-end in GCC is a low priority for GCC developers. Also, GCC does not integrate smoothly into Apple's integrated development environment (IDE).[17] Finally, GCC is licensed under the terms of GNU General Public License (GPL) version 3, which requires developers who distribute extensions for, or modified versions of, GCC to make their source code available, whereas LLVM has a BSD-like license[18] which does not have such a requirement.

Apple chose to develop a new compiler front end from scratch, supporting C, Objective-C and C++.[17] This "clang" project was open-sourced in July 2007.[19]

Clang is intended to work on top of LLVM.[18] The combination of Clang and LLVM provides most of the toolchain, to allow replacing the full GCC stack. Because it is built with a library-based design, like the rest of LLVM, Clang is easy to embed into other applications. This is one reason why most OpenCL implementations are built with Clang and LLVM.[citation needed]

One of Clang's main goals is to provide a library-based architecture,[20] to allow the compiler to be more tightly tied to tools that interact with source code, such as an integrated development environment (IDE) graphical user interface (GUI). In contrast, GCC is designed to work in a compile-link-debug workflow, and integrating it with other tools is not always easy. For instance, GCC uses a step called fold that is key to the overall compile process, which has the side effect of translating the code tree into a form that looks unlike the original source code. If an error is found during or after the fold step, it can be difficult to translate that back into one location in the original source. Also, vendors using the GCC stack within IDEs use separate tools to index the code, to provide features like syntax highlighting and autocomplete.

Clang is designed to retain more information during the compiling process than GCC, and to preserve the overall form of the original code. The goal of this is to make it easier to map errors back into the original source. The error reports offered by Clang are also aimed to be more detailed and specific, as well as machine-readable, so IDEs can index the output of the compiler during compiling. Modular design of the compiler can offer source code indexing, syntax checking, and other features normally associated with rapid application development systems. The parse tree is also more suitable for supporting automated code refactoring, as it directly represents the original source code.

Clang compiles only C-like languages, such as C, C++, Objective-C, Objective-C++, OpenCL, CUDA, and HIP. For other languages, like Ada, LLVM remains dependent on GCC or another compiler frontend. In many cases, Clang can be used or swapped out for GCC as needed, with no other effects on the toolchain as a whole.[citation needed] It supports most of the commonly used GCC options. A sub-project Flang by Nvidia and The Portland Group added Fortran support.[21]

Clang is designed to be highly compatible with GCC.[9] Clang's command-line interface is similar to and shares many flags and options with GCC. Clang implements many GNU language extensions and enables them by default. Clang implements many GCC compiler intrinsics purely for compatibility. For example, even though Clang implements atomic intrinsics which correspond exactly with C11 atomics, it also implements GCC's __sync_* intrinsics for compatibility with GCC and libstdc++. Clang also maintains ABI compatibility with GCC-generated object code. In practice Clang can often be used as a drop-in replacement for GCC.[22]

Clang's developers aim to reduce memory footprint and increase compilation speed compared to competing compilers, such as GCC. In October 2007, they report that Clang compiled the Carbon libraries more than twice as fast as GCC, while using about one-sixth GCC's memory and disk space.[23] By 2011, Clang seems to retain this advantage in compiler performance.[24][25] As of mid-2014, Clang still consistently compiles faster than GCC in a mixed compile time and program performance benchmark.[26] However, by 2019, Clang is significantly slower at compiling the Linux Kernel than GCC while remaining slightly faster at compiling LLVM.[27]

While Clang has historically been faster than GCC at compiling, the output quality has lagged behind. As of 2014, performance of Clang-compiled programs lagged behind performance of the GCC-compiled program, sometimes by large factors (up to 5.5x),[26] replicating earlier reports of slower performance.[24] Both compilers have evolved to increase their performance since then, with the gap narrowing:

In 2021 there was a benchmark made to compare LLVM 2.7 vs LLVM 11 performance and compile times. The conclusion was LLVM 11 tends to take 2x longer to compile code with optimizations, and as a result produces code that runs 10-20% faster (with occasional outliers in either direction), compared to LLVM 2.7 which is more than 10 years old.[29]

This table presents only significant steps and releases in Clang history.

| Date | Highlights |

|---|---|

| 11 July 2007 | Clang frontend released under open-source licence |

| 25 February 2009 | Clang/LLVM can compile a working FreeBSD kernel.[30][31] |

| 16 March 2009 | Clang/LLVM can compile a working DragonFly BSD kernel.[32][33] |

| 23 October 2009 | Clang 1.0 released, with LLVM 2.6 for the first time. |

| December 2009 | Code generation for C and Objective-C reach production quality. Support for C++ and Objective-C++ still incomplete. Clang C++ can parse GCC 4.2 libstdc++ and generate working code for non-trivial programs,[18] and can compile itself.[34] |

| 2 February 2010 | Clang self-hosting.[35] |

| 20 May 2010 | Clang latest version built the Boost C++ libraries successfully, and passed nearly all tests.[36] |

| 10 June 2010 | Clang/LLVM becomes integral part of FreeBSD, but default compiler is still GCC.[37] |

| 25 October 2010 | Clang/LLVM can compile a working modified Linux kernel.[38] |

| January 2011 | Preliminary work completed to support the draft C++0x standard, with a few of the draft's new features supported in Clang development version.[39][11] |

| 10 February 2011 | Clang can compile a working HotSpot Java virtual machine.[24] |

| 19 January 2012 | Clang becomes an optional component in NetBSD cross-platform build system, but GCC is still default.[40] |

| 29 February 2012 | Clang 3.0 can rebuild 91.2% of the Debian archive.[41] |

| 29 February 2012 | Clang becomes default compiler in MINIX 3[42] |

| 12 May 2012 | Clang/LLVM announced to replace GCC in FreeBSD.[43] |

| 5 November 2012 | Clang becomes default compiler in FreeBSD 10.x on amd64/i386.[44] |

| 18 February 2013 | Clang/LLVM can compile a working modified Android Linux Kernel for Nexus 7.[45][46] |

| 19 April 2013 | Clang is C++11 feature complete.[47] |

| 6 November 2013 | Clang is C++14 feature complete.[48] |

| 11 September 2014 | Clang 3.5 can rebuild 94.3% of the Debian archive. The percentage of failures has dropped by 1.2% per release since January 2013, mainly due to increased compatibility with GCC flags.[49] |

| October 2016 | Clang becomes default compiler for Android[50] (and later only compiler supported by Android NDK[51]). |

| 13 March 2017 | Clang 4.0.0 released |

| 26 July 2017 | Clang becomes default compiler in OpenBSD 6.2 on amd64/i386.[52] |

| 7 September 2017 | Clang 5.0.0 released |

| 19 January 2018 | Clang becomes default compiler in OpenBSD 6.3 on arm.[53] |

| 5 March 2018 | Clang is now used to build Google Chrome for Windows.[54] |

| 8 March 2018 | Clang 6.0.0 released |

| 5 September 2018 | Clang is now used to build Firefox for Windows.[55] |

| 19 September 2018 | Clang 7.0.0 released |

| 20 March 2019 | Clang 8.0.0 released |

| 1 July 2019 | Clang becomes default compiler in OpenBSD 6.6 on mips64.[56] |

| 19 September 2019 | Clang 9.0.0 released with official RISC-V target support.[57] |

| 29 February 2020 | Clang becomes the only C compiler in the FreeBSD base system, with the removal of GCC.[58] |

| 24 March 2020 | Clang 10.0.0 released |

| 2 April 2020 | Clang becomes default compiler in OpenBSD 6.7 on powerpc.[59] |

| 12 October 2020 | Clang 11.0.0 released |

| 21 December 2020 | Clang becomes default compiler in OpenBSD 6.9 on mips64el.[60] |

| 14 April 2021 | Clang 12.0.0 released |

In addition to the language extensions listed here, Clang aims to support a broad range of GCC extensions.

While the overall GCC compatibility is excellent and the compile times are impressive, the performance of the generated code is still lacking behind a recent GCC version.

Binaries from LLVM-GCC and Clang both struggled to compete with GCC 4.5.0 in the timed HMMer benchmark of a Pfam database search. LLVM-GCC and Clang were about 23% slower(...)Though LLVM / Clang isn't the performance champion at this point, both components continue to be under very active development and there will hopefully be more news to report in the coming months

By: Wikipedia.org

Edited: 2021-06-18 15:14:48

Source: Wikipedia.org